Europa erkennt endlich die Bedeutung der Kreislaufwirtschaft für den Klimaschutz

BRAND STORYLernt Kollege Computer denken?

Weiterlesen

Europa erkennt endlich die Bedeutung der Kreislaufwirtschaft für den Klimaschutz

BRAND STORYAuf Nummer sicher

Weiterlesen

Europa erkennt endlich die Bedeutung der Kreislaufwirtschaft für den Klimaschutz

BRAND STORYUmweltbildung ist ein Thema für Groß und Klein!

Weiterlesen

Menschen & Verantwortung

18. April 2024

Der Medienhype um das Thema KI ist groß. Es vergeht kaum ein Tag, an dem nicht ...

Public Services

17. April 2024

Der batterieelektrische Mercedes-Benz eActros 600 geht in den Kundentest. Die ersten beiden Erprobungsfahrzeuge des im vergangenen ...

Recycling

10. April 2024

Abfalltrennung ist nicht immer einfach. Wer hat sich nicht schon einmal gefragt, ob die soeben geleerte ...

Newsletter

Melden Sie sich ganz unkompliziert zu unserem Newsletter REMONDIS AKTUELL mit Informationen zu Leistungen, Produkten und vielen weiteren Infos an.

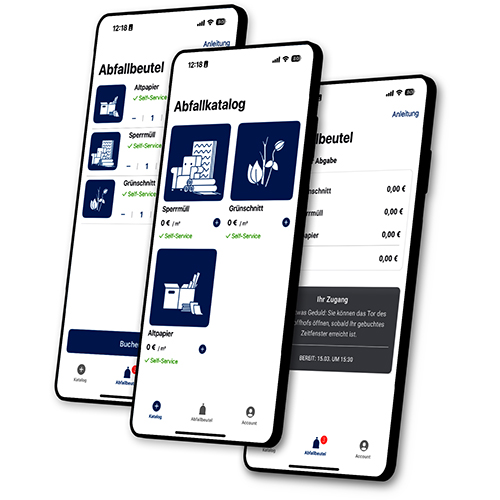

Public Services

26. März 2024

Per App anmelden, Slot buchen, zum Wertstoffhof fahren, Tor mittels Bluetooth öffnen, selbst die Wertstoffe abgeben ...

Industrieservices

26. März 2024

Ein Optimum an Sicherheit und Gesundheit zu schaffen, ist eine herausfordernde Aufgabe. Das gilt besonders für ...

Recycling

25. März 2024

Seit dem 25. März 2024 kooperiert EKO-PUNKT, das Duale System von REMONDIS, mit der Markant Gruppe, ...

Industrieservices

21. März 2024

„Medizinische Einmalgebrauchsprodukte in der Kreislaufwirtschaft“ (MEiK) ist das Forschungsfeld eines Konsortiums aus fünf Unternehmen und zwei ...